In 1869 Manchester’s Deansgate was one of the most squalid slum areas in the city, along with Salford and Hulme. Families were living in cramped houses with poor amenities. Unemployment was high and many relied on the generosity of others to provide them with a meal for their families each day.

In April of that year Alfred Alsop, book seller, publisher, and Methodist, and a few friends conducted their first service in the street, with an aim to preach the Gospel in those slum areas. Alfred realised that his evangelical zeal could not compete with the appalling levels of hunger, poverty and destitution which many in the community endured. He decided to create a charitable movement – Manchester and Salford Street Children’s Mission – that resolved to provide the basic necessities of life: food, shelter and clothing.

Following a first mission site in Lombard Street, the site on Wood Street was acquired in 1873 and a brand-new building built. Accommodation was provided there for homeless boys and later girls, and free dinners, clothing and shoes were provided for hundreds of children and their families. In addition, the Christmas breakfasts and parties, and the Boxing Day toy distributions, became a tradition in Manchester life.

A Christmas Carol, probably the most popular piece of fiction that Charles Dickens ever wrote, was published in 1843. Dickens was involved in charities and social issues throughout his entire life. At the time that he wrote A Christmas Carol he was very concerned with impoverished children who turned to crime and delinquency in order to survive.

Dickens, as well as others, thought that education could provide a way to a better life for these children. The Ragged School movement put these ideas into action. The schools provided free education for children in the inner-city. The movement got its name from the way the children attending the school were dressed. They often wore tattered or ragged clothing.

In September of 1843 Dickens visited the Field Lane Ragged School.

In a letter to his friend, Miss Coutts, he described what he saw at the school:

“I have very seldom seen, in all the strange and dreadful things I have seen in London and elsewhere anything so shocking as the dire neglect of soul and body exhibited in these children. And although I know; and am as sure as it is possible for one to be of anything which has not happened; that in the prodigious misery and ignorance of the swarming masses of mankind in England, the seeds of its certain ruin are sown.”

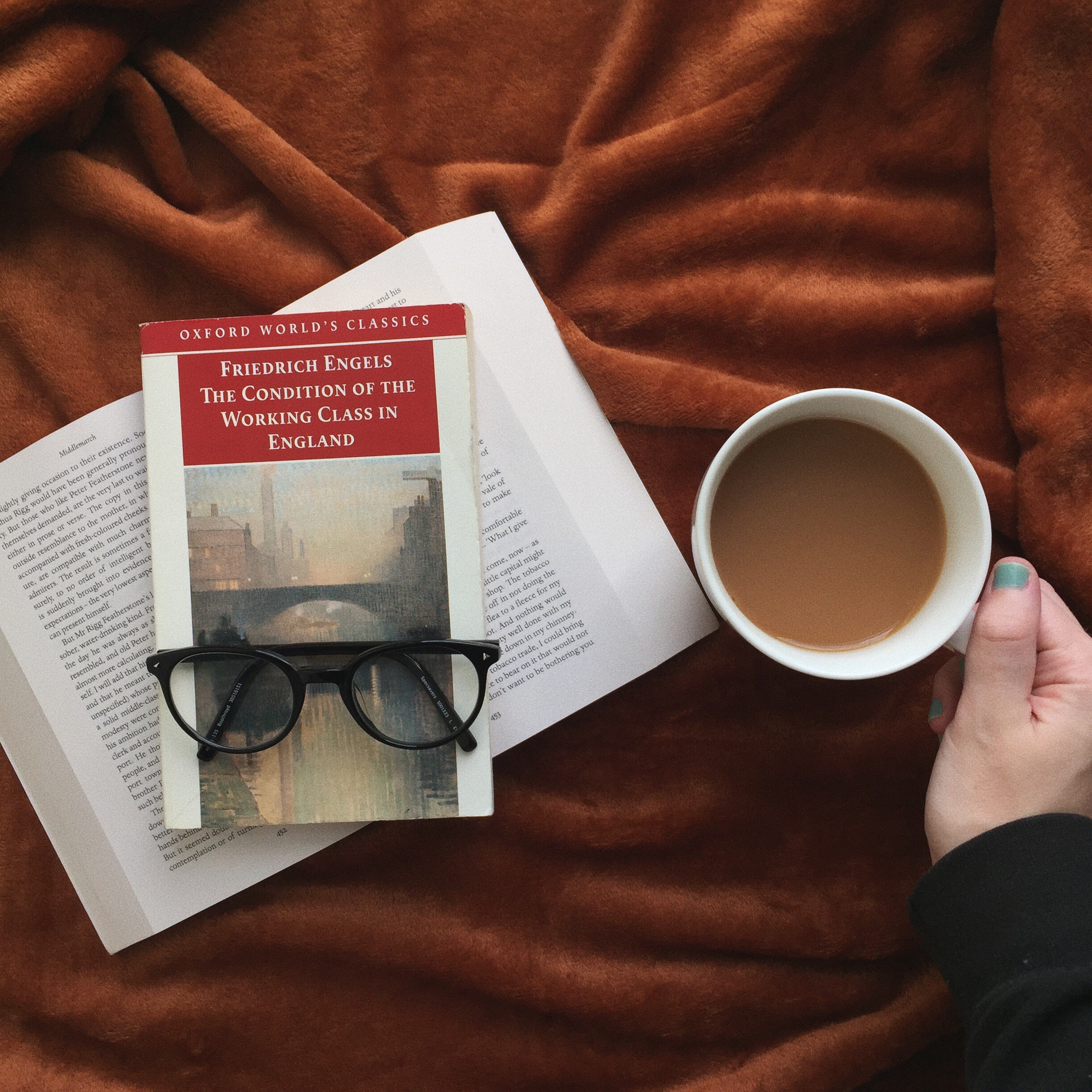

German writer and political theorist Friedrich Engels is perhaps best remembered as the co-author, with Karl Marx, of The Communist Manifesto in 1848. But Engels’s view of capitalism as a justification for the rich to exploit the poor and uneducated had been developed in his first book The Condition of the Working Class in England of 1844.

In often revolutionary language, it draws on his experiences while living in Manchester, then at the heart of the industrial revolution. Engels was horrified by the child labour, environmental damage, low wages, bad conditions, poor health, death rates – and the ‘social and political power of your oppressors’.

Friedrich Engels was the rebellious eldest son of a family of German industrialists. In an attempt to quell his rebellion, and to keep him apart from undesirable friends in Berlin, Engels’s father apprenticed him to a family mill in Salford near Manchester.

There, he gave up ‘the dinner-parties … and champagne of the middle classes’ and instead spent time talking to the workers. Engels discovered a project of industrialisation more extensive than any he had seen in Germany, where the life expectancy of the poorest was as low as it had been during the Black Death (1348–1350).

In The Condition of the Working Class in England, Engels described the living conditions in English industrial towns as ‘the highest and most unconcealed pinnacle of social misery existing in our day’.

0 Comments