WHY should anyone so much as glance at this academic, albeit fairly abbreviated, history of a religious-political entity which ceased to exist hundreds of years ago?

That’s a question addressed by Tayeb El-Hibri in this scholarly evaluation of the Abbasid dynasty and, in so doing, he constantly emphasises the valuable insights to be gleaned from such a study and the contemporary geopolitical relevance of the caliphate concept.

It is fair to say that a number of present-day Islamic and Islamist movements draw inspiration from the Abbasid caliphate as much as their reductionist view of the foundation society under the Prophet Mohammed.

In spite of a bewildering cast list of empires, including assorted Fatimids, Buyids, Ghaznavids and Mamluks, the Abbasids remained the pre-eminent and most influential force in the Muslim world from 750 to 1258 AD, with an Egyptian branch continuing for a further couple of centuries.

At the height of their military and political might, the Abbasids controlled an expanse of land from modern-day Libya, its heartland around Baghdad and along the Silk Route and up to the borders of China.

Yet El-Hibri comprehensively repudiates both contemporary and later Western narratives of an empire that speedily built up to a zenith only to be followed by a prolonged and dissolute contraction in the resources and lands that it controlled and the influence that it wielded.

Understandably, he has no time for such Orientalist narratives.

What is most remarkable about the Abbasids was the frequent cycles of territorial contraction and expansion that they experienced.

The ability of the ruling family and their advisers to adapt to the shifting realities around them was certainly a contribution to their longevity.

El-Hibri sketches in some detail the dynasty’s renaissance in the 10th and 11th centuries under the caliphs al-Qadir, al-Qa’im and al-Muqtadi.

The basis for this revival was the deliberate emphasis placed upon the Abbasids as religious leaders of the Sunni Muslim populations across the globe, as opposed to military warlords.

“We do a disservice to the Abbasid caliphate to judge it as an empire,” El-Hibri emphasises, “it may be more pertinent to view it as an Islamic political institution.”

The moral imperative of being accorded legitimacy in the eyes of the faithful was sparked by the speedy recognition of potential dynastic threats.

An almost dual-control system developed between the caliph and the sultan of whichever group had achieved, frequently fleetingly, territorial dominance.

Usually, such alliances were cemented or facilitated by means of appropriate arranged marriages.

Many chief advisers of the Abbasids professed loyalty to one or another of the Shi’ite branches of Islam yet, as El-Hibri points out, with the exception of the Fatimids of Egypt, the Abbasids strove for, and mostly achieved, a careful balance between an emerging Sunni orthodoxy without significant antagonisms towards other religious groups.

The high status of Baghdad’s large Jewish population was certainly in stark contrast to the pogroms being unleashed on their co-religionists in Europe.

The author provides compelling evidence to show how the Abbasids’ pragmatism resulted in a succession of artistic and scientific advances — inconvenient truths for current Islamophobes.

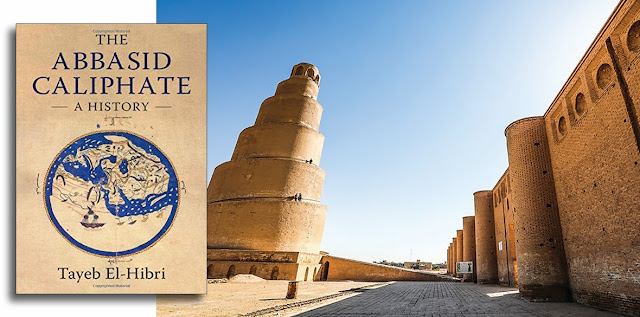

Though the text’s accompanying images are somewhat underwhelming, the book’s comprehensive glossary of terms and a helpful chronological listing of respective caliphs contribute to a highly engaging and illuminating account of a pivotal and still resonant period of history and religion for both the generalist and specialist reader.

The Abbasid Caliphate: A History by Tayeb El-Hibri. Published by Cambridge University Press, £22.99.

0 Comments